1893, India, and the USA

(See also The Crisis of 1893)

In 1892 India was a colony of the United Kingdom.1 It was governed from Calcutta by civil servants appointed in London, but susceptible to pressure from local plantation owners (who were mostly British), importers, and financiers. Prior to European colonization, India had had rulers who circulated silver coins known as rupees; until 1892, the rupee was defined as a unit of silver. In 1816, the UK moved to a gold coin standard, and after 1870, most of the nations of Europe and America did also. The USA went on the gold standard 1 January 1879 after 13 years laborious struggle retiring Civil War greenbacks.2 India, Japan (to 1897), Korea, and the Qing Empire (China + Mongolia) continued to use mostly silver money. So did Latin America.3

India was at this time the largest market for silver in the world; the USA was the second largest. Russia, like the USA, had a large internal system of silver currency despite officially being on the gold standard. During the period 1873-1902, silver prices would decline relative to gold, pushing more countries to adopt the gold standard and demonetize silver. This further suppressed silver prices, until nearly the entire global consumption of silver was for commercial purposes (jewelry, chemicals, and photography).

| Chart adapted from Milton Friedman, Money Mischief: episodes in monetary history, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, (1994), p.72 Note: the ratio of 16-to-one was a legal ratio that applied at the beginning of this period. At earlier times in the 19th century, lower ratios obtained in bimetallic countries. |

India's situation was especially problematic because it was economically and administratively integrated with the British gold zone. The US situation was problematic because it had a large residue of silver currency and a major silver mining economy; and because it was such a magnet for overseas investment. It was also unusual for a large country of the day in having representative democracy. Hence, it was politically difficult for the executive branch to impose austerity conditions required for a pure gold monetary system.

India operated under extraordinarily open markets in 1892; its duties on imported goods were virtually nil, and it had a policy of free coinage (no seigniorage; the rupee therefore floated against the pound sterling).4 The system was not self-correcting; India's government had to pay for the costs of occupying and exploiting its subjugated peoples, and these costs had been incurred in sterling. This was being paid off in a rupee whose value was falling. In the 19th century literature, moreover, one reads of constant "crises" in Victorian finances, in which national governments were constantly struggling to maintain either adequate reserves of gold, or else resisting an inflationary spike at home. In India, the part of the system that was particularly vulnerable were "council bills," or bills of exchange drawn against the national debt of India held in London. These were adjusted automatically in accordance with the daily exchange rate of silver, which was just fine for commercial transactions; but for government business, it was a chronic strain. Officers, for example, had to be paid in rupees and their pay schedule was set by legislation in Westminster.

The USA operated under extraordinarily closed markets; the McKinley Tariff (1890) was the highest tariff schedule in the nation's history. Countervailing the successful Republican push for ever-higher tariffs was populist pressure for cheap money (as desired by farmers and business projectors) based on silver (as desired by the Western silver interests). This took the form of the Sherman Silver Purchase Act, which required the Treasury to buy 4.5 million ounces of silver per month, to be paid for in legal tender treasury notes.5 The effect was, unfortunately, to create a de facto bimetallic standard with silver overvalued relative to gold. Hence, arbitrageurs pumped gold out of the US banking system, since they could buy undervalued gold with overvalued silver.

(See "Precious Metals Arbitrage")

At the same time gold was being pumped out of the USA, silver was flowing into India as a result of that country's long-running trade surplus with the rest of the world (see chart below).

| Click on image to enlarge Values are in UK pounds sterling | ||||||

| India: Influx of Precious Metals Prior to 1893 Crisis | ||||||

| Five Years ended 31st March | Average Gold Value of the Rupee | Average Net Imports of Gold per Annum | Average Net Imports of Silver per Annum | |||

| beginning | ending | £ | (Rupees) | (£) | (Rupees) | (£) |

| 1860 | 1864 | 0.0994 | 5,889,538 | 585,273 | 10,181,781 | 1,011,814 |

| 1865 | 1869 | 0.0976 | 5,835,117 | 569,653 | 9,981,112 | 974,406 |

| 1870 | 1874 | 0.0950 | 3,073,776 | 292,009 | 3,598,271 | 341,836 |

| 1875 | 1879 | 0.0874 | 639,595 | 55,898 | 6,408,692 | 560,093 |

| 1880 | 1884 | 0.0824 | 4,128,613 | 340,181 | 6,205,349 | 511,295 |

| 1885 | 1889 | 0.0762 | 3,083,670 | 234,963 | 6,896,685 | 525,499 |

| 1890 | 0.0690 | 4,615,304 | 318,571 | 10,937,876 | 754,987 | |

| 1891 | 0.0754 | 5,636,172 | 424,803 | 14,175,136 | 1,068,392 | |

| 1892 | 0.0697 | 2,413,792 | 168,292 | 9,022,184 | 629,034 | |

| 1893 | 0.0624 | -2,812,683 | -175,582 | 12,863,569 | 803,008 | |

Report of the West India Royal Commission Great Britain, Eyre ξ Spottiswoode (1897) Appendix. C, p.209 table III

| ||||||

The conversion to what was, in effect, a gold exchange standard, reversed the balance of trade and the flow of gold. This, of course, made the next several years a crisis because India, while possessing decades of accumulated reserves of silver, had demonetized it and now required gold—which was leaving the country, not entering it.

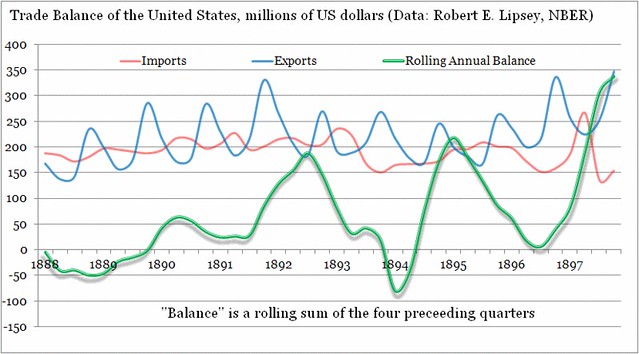

India's demonetization of silver was widely seen as the the immediate trigger of the Crisis in the USA. The US Treasury, ultimately liable for the total supply of paper currency, was faced with a sharp increase in the flow of gold out of the country for purposes of arbitrage; it was providing a handsome subsidy for doing so.6 Strangely, the rate at which this arbitration occurred was quite low. One would have expected the Treasury to be wiped out within a few weeks, given the arbitrage opportunities; instead, there was a dangerous stream out of the Treasury for many months, but nothing like the capital flights from Asian countries during the 1997-1998 crisis, or from Argentina in 2002. It seems reasonable to surmise this was because metals arbitrage was logistically very difficult.

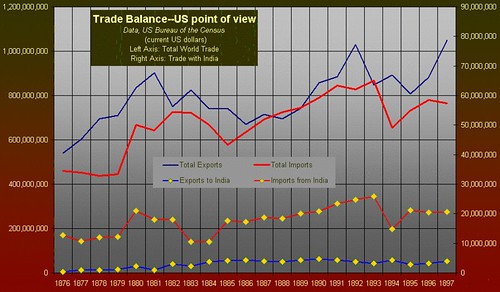

Values are in current US dollars

While the USA usually ran a trade surplus with the rest of the world, India ran large surpluses with the USA (and most other nations) every year. Data from the 1889 and 1897 Statistical Abstracts of the USA |

A limiting factor, however, was always the very large trade surpluses the USA had with the rest of the world; this meant that Usonian institutions (and ultimately, the US Treasury as the supreme reserve) held a massive surplus of liabilities against non-Usonian individuals and institutions. This would not have prevented massive metals arbitrage over time, since large claims on US assets did exist in the hands of foreigners; but these (a) were tied up as foreign direct investment (FDI) or portfolio investment in the USA, or (b) tended to be small enough that they restricted arbitrage to lots of small, marginally profitable steps.

However, note that India was a rare exception: trade between the USA and India was small, but consisted of huge surpluses (relative to the volume of US exports to India. This was in large measure an artifact of the underdevelopment of India; but that is outside the scope of this post.

NOTES:

- At this time, "India" included Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Burma (Myanmar). For a map online, see the Schwartzberg Atlas. About one third of Indians lived in the 500 princely states that enjoyed financial and internal autonomy from the capital in Calcutta. India and Burma[h] shared a currency, the rupee. Princely states also issued rupees, although the value was supposed to be the same for all varieties of the rupee. See also The imperial guide to India, including Kashmir, Burma and Ceylon, John Murray (London, 1904) p.195; also, Lawson (1894), p.443

- Milton Friedman, Anna Jacobson Schwartz (1963), "The Greenback Period"

- Matias Romero, The silver standard in Mexico, The Knickerbocker Press (1898); for Japan and Korea, see n.587; for China, see n.606; for several Latin American states (other than Mexico), see p.576. Silver standard nations often had enormous local supplies of silver, such as Mexico; or else, were more likely to use metal coins to the exclusion of paper money or bills of exchange. The Qing Empire had floating trimetallism at the time of the 1893 crisis, meaning that copper, silver, and gold monetary systems existed concurrently with no fixed relationship to each other.

- Lawson (1894), p.453; floating of rupee pre-1892, see Palgrave (1894-III), p.396. For a modern summary, see Tapan Raychaudhuri, Dharma Kumar, Meghnad Desai, Irfan Habib, The Cambridge economic history of India, Volume 2, Cambridge University Press (1983), p.587. As a general rule, countries with the power to do so implemented tariffs; countries under foreign occupation, such as India, or else under foreign hegemony, such as Japan (1856-1897), had free trade imposed at gun point.

- For the McKinley Tariff, see Joanne R. Reitano, The tariff question in the Gilded Age: the great debate of 1888, Penn State University Press (1994), p.129. The previous tariff had been 38%, so prices of imported goods were effectively increased 8.33%. For the Sherman Silver Purchase Act, see Wesley Clair Mitchell, Business cycles, Burt Franklin (1913/1970), p.52.

- For the perception of India's demonetization as trigger, see Conant (1909, pp.677-67). Regarding gold flows, see Friedman ξ Schwartz (1963) p.108 and table A-4 (Appendix A, p.769). Friedman ξ Schwartz do not mention the role of gold arbitrage, but include a lengthy footnote on the distinction between external and internal drains in the Treasury's gold supply. According to some commentators, such as Charles Conant (1909, p.671) and A.D. Noyes (Forty Years of American Finance, Putnam, 1909, pp.159-173), the problem was that the silver policy caused a loss of confidence in the integrity of the money supply. Friedman ξ Schwartz emphasize that silver probably only accounted only for the external (foreign) drain of gold

SOURCES ξ ADDITIONAL READING

Charles Conant, A History of Modern Banks of Issue, G.P. Putnam ξ Sons (1909), esp. "The Crisis of 1907," p.698. Vital resource, although chapters on crises require close reading. Very useful to cross-reference with Friedman ξ Schwartz (1963).

Milton Friedman ξ Anna Jacobson Schwartz, A monetary history of the United States, 1867-1960, Princeton University Press (1971)

W.R. Lawson, "The Indian Currency Muddle," Blackwood's Edinburgh (March 1894), p.440-454. Describes the circumstances leading up to and following the momentous Indian suspension of silver coinage in 1892, which played a significant role in the 1893 Crisis.

R.H.I. Palgrave, Dictionary of Political Economy, Vol. 1, Macmillan (1894); "Exchange between Great Britain and British India," p.776; Vol. 3, "Silver, as Standard," p.395

Labels: anthropology, economics, history